SHARING OUR VALUES: TEAMWORK

SHARING OUR VALUES: TEAMWORK

At Charter School Capital, we hold each other accountable to core company values as the driving force and foundation of what we do. These values are our guiding principles as we work together to more effectively support the growth and development of our charter school partners. And, as a result, Charter School Capital is a proven catalyst for charter school growth. In CSC’s ten years, we very proud to say that we’ve helped finance the education of more than 800,000 students in over 600 charter schools across the United States.

We measure everything we do by these core values:

• Best-in-Class

• Empowerment

• Innovation

• Teamwork

• Accountability

In this blog series, we wanted to spotlight how all of us at CSC work to exemplify these core values. For this, the third post of the series, we’ll dive deeper into what teamwork means to us and how we embody and reflect this goal both internally and what that means for our charter school partners.

Teamwork seems to be at the core of everything we do here at CSC. Each team relies on each other to support our charter school partners in their success.

A culture of teamwork

To get some expert insight into how we strive to live up to the value of teamwork, I was pleased to sit down with Marci Phee, Client Services Director here at Charter School Capital. Once a school comes on board with us, Marci’s team ensures that the funding is working for the school in the way that they want it to; that they’re getting their funding, assistance, and support on time; and that our team is available to help the school with whatever needs they may have.

To get some expert insight into how we strive to live up to the value of teamwork, I was pleased to sit down with Marci Phee, Client Services Director here at Charter School Capital. Once a school comes on board with us, Marci’s team ensures that the funding is working for the school in the way that they want it to; that they’re getting their funding, assistance, and support on time; and that our team is available to help the school with whatever needs they may have.

Marci – selected by CSC leadership as the embodiment of the value of teamwork here at CSC – has been with Charter School Capital for three years, and has been key in building our team culture. One of her early missions was to help her team build a deep but practical understanding of the value gained from partnering with other teams across the organization and how working as a team would help us better achieve our goals.

Sitting down with Marci, I was curious to know:

• How one goes about building a high-performing team

• How teamwork helps us directly support our clients

• How being passionate about our mission plays into our value of teamwork

• What actionable things that we do to support teamwork

A shared vision

I began our conversation by asking Marci how the team stays on course to do what is in the best interest of the company and our schools. And her immediate response was all about the shared vision – or the collective understanding of the direction we’re all headed—and it’s all about how we serve our customers.

“For our team to work well together, the first step is for everyone to understand where we’re all going. That means when we bring a school on board and commit to funding that school, we’re all in. Everyone knows that the goal is not just to deliver funding, it’s to deliver what each school needs or wants, whether that is a renovated gym or some operational help to get through the end of the school year.

When we commit and say, ‘yes, we’ll provide that funding,’ what we’re really saying is, ‘yes, we will get you where you want to go.’ And every member of our team—whether it’s underwriting or finance or the executives or the account managers—knows what the end goal is. That’s where we’re going. A common goal makes it much easier to work together as a team.”

A dedicated team

One of the things I’ve come to understand in my few months here at CSC– that perhaps makes us a bit different than others in our industry – is the comprehensive team of finance professionals we put in place to work with every single one of our school partners. This knowledgeable, dedicated team works together with our schools to find sustainable solutions to ensure that they succeed in the near term and as they grow. I wanted to ask Marci to clarify how that team is assembled and how they create the framework that helps them work together in the best interest of our school partners.

“Every school in our portfolio has essentially three charter school capital members who are assigned to their account and know it very well. Very, very well. There’s always a primary point of contact who will be the dedicated account manager. That is the one person you can always call. That’s just part of a core, client-facing team that includes the account manager, a financial analyst, and an underwriter. If something comes up and the school needs a different financing option, or they have questions regarding corporate structure or education, they know that their team will support them. This is the case throughout the life of our clients, even as their financial needs change.”

The three C’s

Marci shares, more specifically, how this multi-faceted team structure works so effectively. It comes down to three words: Cooperation, Collaboration, and Communication – the three C’s.

“Because there’s an assigned team that is responsible for knowing the school, it just makes it easier to cooperate. Everyone knows who their partner is cross-functionally. And, from a collaboration standpoint, everybody has the same goal and everybody’s willing to help and have open lines of communication. People here show up to meetings, are responsive to emails, have informal text messages, just walk by and say, ‘Hey, I need your help.’ We share at water cooler conversations, joint coffee runs, and chats riding up in the elevator—and all of that pieces together to deliver the best product in partnership to the school.”

Grit, Creativity, Partnership

Marci has built a high-performing team of people who are dedicated, hard-working, and are master collaborators. I wanted to know what characteristics she looks for when building a team, and what qualities she thinks makes a great team player.

And, her first, out-of-the-gate response was “Grit. It’s that ‘never die’ mentality. There has to be a solution. There has to be a way. There’s always a way. I need that creativity and creative problem solving in each of my team members.”

This immediately reminded me of our interview with John Caughie on the value of innovation here at CSC and how it’s one of the reasons we’re different. We see solutions where other financial institutions may see red flags. We pride ourselves on supporting team members to find those innovative, creative solutions our schools need to be successful and sustainable.

And, in addition to grit and creativity, Marci was clear that having an “inclination towards partnership” was also key. I asked her to explain what she meant by that.

“It’s really important that our dedicated account managers partner with the school’s business, with the school’s goals. If I stop an account manager in the hallway and ask, ‘What is the objective for X, Y, Z charter school for the year?’ they need to be able to articulate exactly what it is. This is not about money, this is about partnering with the school to understand what they’re trying to achieve. And then it’s our job to provide the tools and resources to help them get there. But you can only do that through a true partnership. You have to establish trust and work as a team, with the client. So, I need that inclination towards partnership to really stand alongside our school leaders and decision makers and get them where they want to go, day in and day out.

It’s all about the students

A shared vision, a dedicated team of professionals, and student focus are all vital to our embodiment of the teamwork value. But all that would mean nothing if we didn’t truly love partnering with our schools and the students they’re educating.

Marci explains, “In the three years I’ve done this, our efforts have always tied to a student outcome in some way. When you understand student success as an organization, and your team understands that student success is the heartbeat of our organization, and we partner with the school and they understand how we feel about student success, and everybody’s on the same page, it’s just more efficient. There’s a lot more trust, and honestly, it’s a lot more fun!

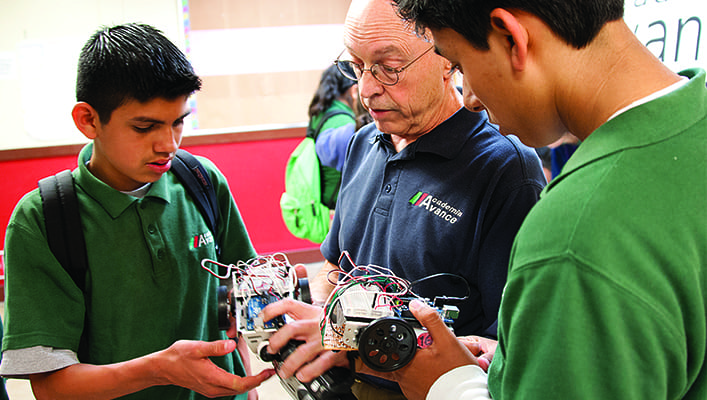

One of our favorite things to do is to go to the school. You are just very happy to see the client and it’s even better when you get to tour the schools and meet the students and see what our funding has done to help them move forward. Or you’re standing there with the school leaders on a big plot of land and they’re saying ‘This is going to be a performing arts center,’ you get to stand there with them and say, ‘yeah, that’s going to be so great.’”

Teamwork does make the dream work

So, it’s clear that we have a mission-driven dedicated team, who cooperate, collaborate, and communicate, but I must conclude this post with the one single thing that is the heart and soul of everything we do—the students.

“One of our driving metrics of students served. I haven’t encountered a single school relationship where the ask for the funding or the need for the funding was not somehow tied to better serving their existing students or to serve more students in the community. Our focus is always on the needs of the school and we will adjust our product based on that need—and that need is always tied to a student. Always.” shares Marci.

What I’ve really taken away from my energizing chat with Marci, is that teamwork really does make the dream work here. I know, such a cliché. But it’s true! Because of our internal investment in teamwork and a shared vision – where we always have the students at the forefront – we’re able to support schools when and how they need it, and work as a team with charter school leaders to make their dreams for their schools happen.

Conclusion

The positivity and chemistry of the entire CSC team is both motivational and inspirational. I love that I have the honor to be part – even a small one – of such a mission-driven, team-focused group of professionals.