Strengthening the Roots of the Charter-School Movement

Strengthening the Roots of the Charter-School Movement

Editor’s Note: This post about the feasibility of charter school expansion was originally published here by EdNext and written by Derrell Bradford. It ponders the question as to whether the charter school movement has the access to the political and grassroots support, capital resources, experts, and critical mass to sustain its growth. It also looks at the challenges that single-site charter schools are facing in contrast to their charter management organization (CMO) or education management organization (EMO) member school counterparts.

Our mission is to see continued charter school expansion, the overall growth of the charter school movement, and more students better served by having educational choice. We think it’s vital to keep tabs on the pulse of all things related to charter schools, including informational resources, and how to support charter school growth and the advancement of the charter school movement as a whole. We hope you find this—and any other article we curate—both interesting and valuable. Please read on to learn more.

Over the past quarter century, charter schools have taken firm root in the American education landscape. What started with a few Minnesota schools in the early 1990s has burgeoned into a nationwide phenomenon, with nearly 7,000 charter schools serving more than three million students in 43 states and the nation’s capital.

Twenty-five years isn’t a long time relative to the history of public and private schooling in the United States, but it is long enough to merit a close look at the charter-school movement today and how it compares to the one initially envisaged by many of its pioneers: an enterprise that aspired toward diversity in the populations of children served, the kinds of schools offered, the size and scale of those schools, and the background, culture, and race of the folks who ran them.

Without question, the movement has given many of the country’s children schools that are now among the nation’s best of any type. This is an achievement in which all charter supporters can take pride.

It would be wrong, however, to assume that the developments that have given the movement its current shape have come without costs. Every road taken leaves a fork unexplored, and the road taken to date seems incomplete, littered with unanswered and important questions.

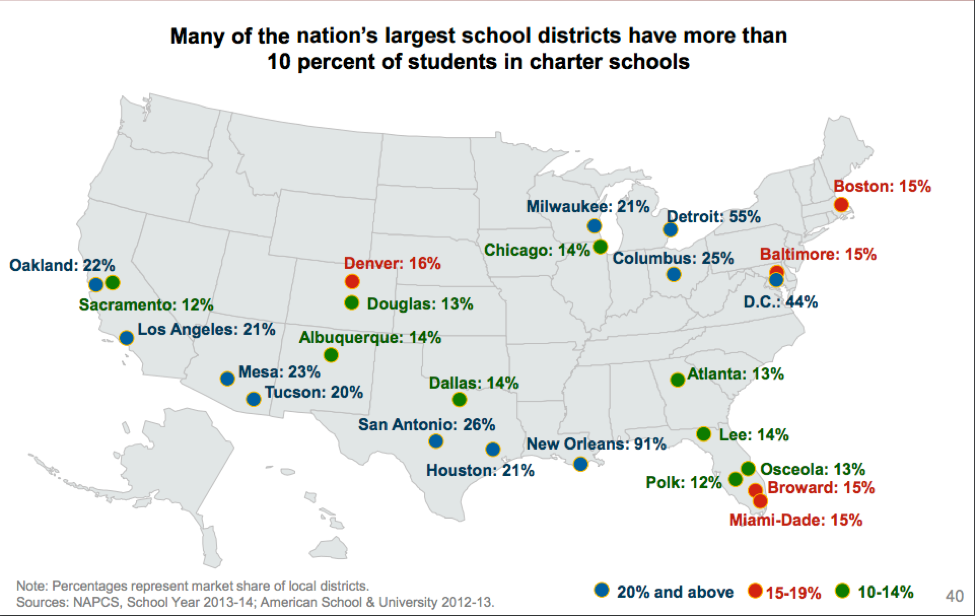

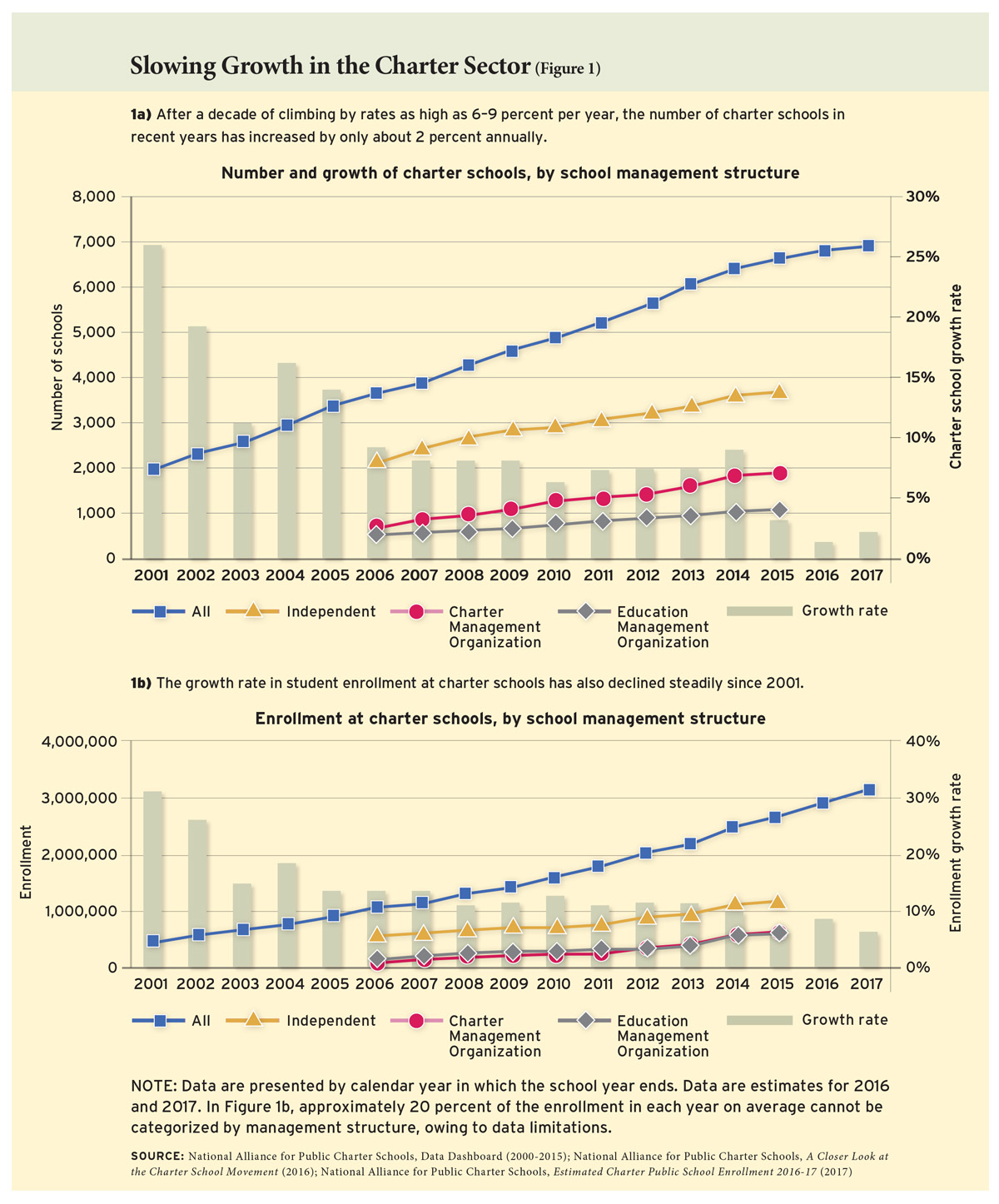

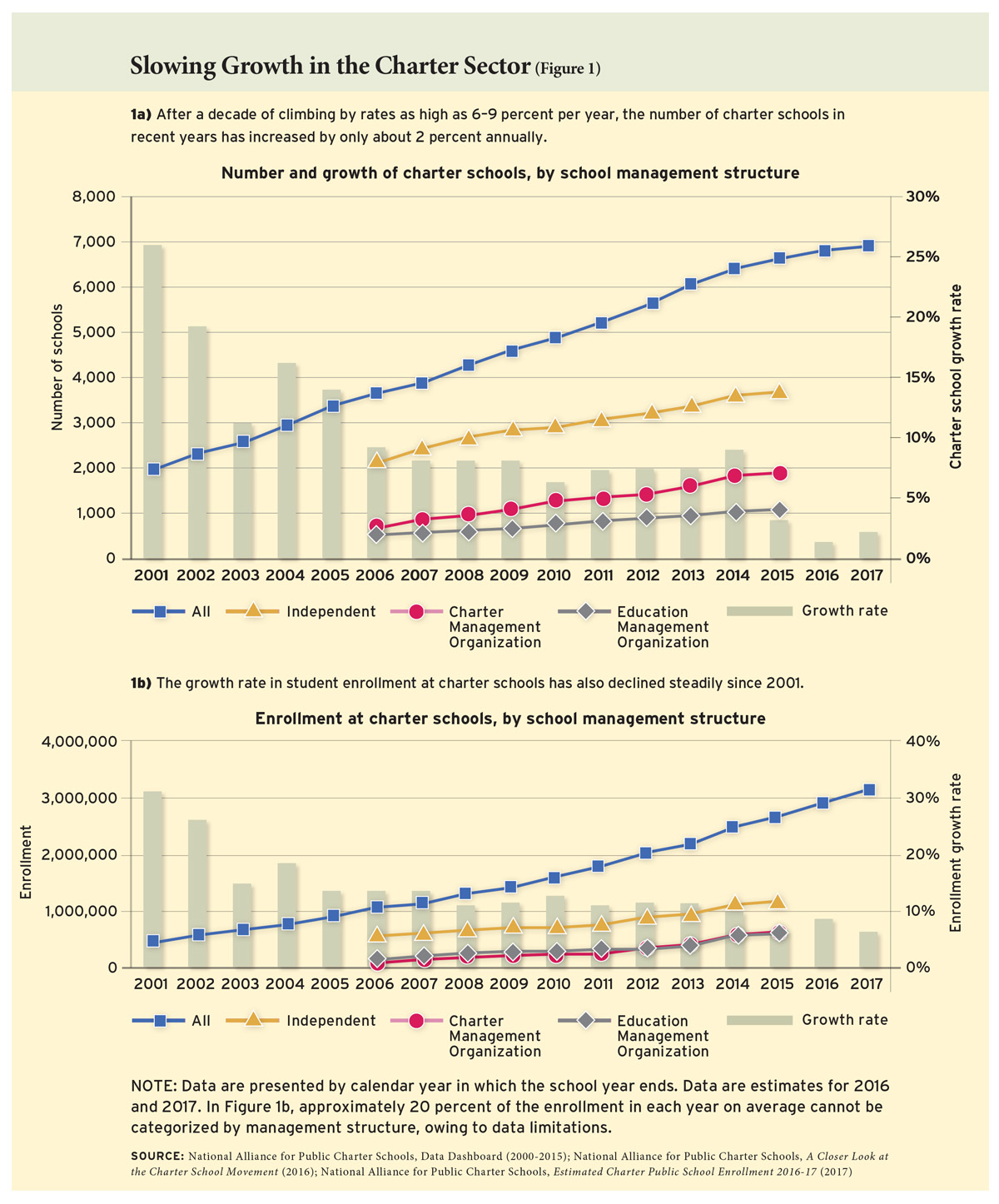

While the charter sector is still growing, the rate of its expansion has slowed dramatically over the years. In 2001, the number of charter schools in the country rose by 26 percent, and the following year, by 19 percent. But that rate steadily fell and now languishes at an estimated 2 percent annually (see Figure 1). Student enrollment in charter schools continues to climb, but the rate of growth has slowed from more than 30 percent in 2001 to just 7 percent in 2017.

And that brings us to those unanswered questions: Can the charter-school movement grow to sufficient scale for long-term political sustainability if we continue to use “quality”—as measured by such factors as test scores—as the sole indicator of a successful school? What is the future role of single-site schools in that growth, given that charter management organizations (CMOs) and for-profit education management organizations (EMOs) are increasingly crowding the field? And finally, can we commit ourselves to a more inclusive and flexible approach to charter authorizing in order to diversify the schools we create and the pool of prospective leaders who run them?

In this final query, especially, we may discover whether the movement’s roots will ever be deep enough to survive the political and social headwinds that have threatened the chartering tree since its first sprouting.

One School, One Dream

Howard Fuller, the lifelong civil rights activist, former Black Panther, and now staunch champion of school choice, once offered in a speech: “CMOs, EMOs . . . I’m for all them O’s. But there still needs to be a space for the person who just wants to start a single school in their community.”

In Fuller’s view, one that is shared by many charter supporters, the standalone or single-site school, and an environment that supports its creation and maintenance, are essential if we are to achieve a successful and responsive mix of school options for families.

But increasingly, single-site schools appear to suffer a higher burden of proof, as it were, to justify their existence relative to the CMOs that largely set the political and expansion strategies for the broader movement. Independent schools, when taken as a whole, still represent the majority of the country’s charter schools—55 percent of them, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. But as CMOs continue to grow, that percentage is shrinking.

Examining the role that single-site schools play and how we can maintain them in the overall charter mix is not simple, but it uncovers a number of factors that contribute to the paucity—at least on the coasts—of standalone schools that are also led by people of color.

Access to Support

If there is a recurring theme that surfaces when exploring the health and growth of the “mom-and-pops”—as many charter advocates call them—it’s this: starting a school, any school, is hard work, but doing it alone comes with particularly thorny challenges.

“Starting HoLa was way harder than any of us expected,” said Barbara Martinez, a founder of the Hoboken Dual Language Charter School, or HoLa, an independent charter school in Hoboken, New Jersey. “We ran into problems very early on and had to learn a lot very, very quickly.” Martinez, who chairs HoLa’s board and also works for the Northeast’s largest charter network, Uncommon Schools, added: “When a CMO launches a new school, they bring along all of their lessons learned and they open with an already well-trained leader. At HoLa, there was no playbook.”

Michele Mason, executive director of the Newark Charter School Fund, which supports charter schools in the city and works extensively with its single-site charters, made a similar point, noting that many mom-and-pops lack the human capital used by CMOs to manage the problems that confront any education startup. “[Prior to my arrival we were] sending in consultants to help school leaders with finance, culture, personnel, boards,” Mason said. “We did a lot of early work on board development and board support. The CMOs don’t have to worry about that so much.”

Mason added that the depth of the talent pool for hiring staff is another advantage that CMOs enjoy over the standalones. “Every personnel problem—turnover, et cetera—is easier when you have a pipeline.”

Access to Experts

Many large charter-school networks can also count on regular technical support and expertise from various powerhouse consultants and consulting firms that serve the education-reform sector. So, if knowledge and professional support are money, some observers believe that access to such wired-in “help” means the rich are indeed getting richer in the charter-school world.

Leslie Talbot of Talbot Consulting, an education management consulting practice in New York City, said, “About 90 percent of our charter work is with single-site schools or leaders of color at single sites looking to grow to multiple campuses. We purposely decided to focus on this universe of schools and leaders because they need unique help, and because they don’t have a large CMO behind them.” Talbot is also a member of the National Charter Collaborative, an organization that “supports single-site charter-school leaders of color who invest in the hopes and dreams of students through the cultural fabric of their communities.”

What are the kinds of support that might bolster a mom-and-pop’s chances of success? “There are lots of growth-related strategic-planning and thought-partnering service providers in [our area of consulting],” offered Talbot. “Single-site charter leaders, especially those of color, often are isolated from these professional development opportunities, in need of help typically provided by consulting practices, and unable to access funding sources that can provide opportunities” to tap into either of those resources.

Connections and Capital

The old bromide “It’s who you know” certainly holds true in the entrepreneurial environment of charter startups. As with any risky and costly enterprise, the power of personal and professional relationships can open doors for school leaders. Yet these are precisely the relationships many mom-and-pop, community-focused charter founders lack. And that creates significant obstacles for prospective single-site operators.

The old bromide “It’s who you know” certainly holds true in the entrepreneurial environment of charter startups. As with any risky and costly enterprise, the power of personal and professional relationships can open doors for school leaders. Yet these are precisely the relationships many mom-and-pop, community-focused charter founders lack. And that creates significant obstacles for prospective single-site operators.

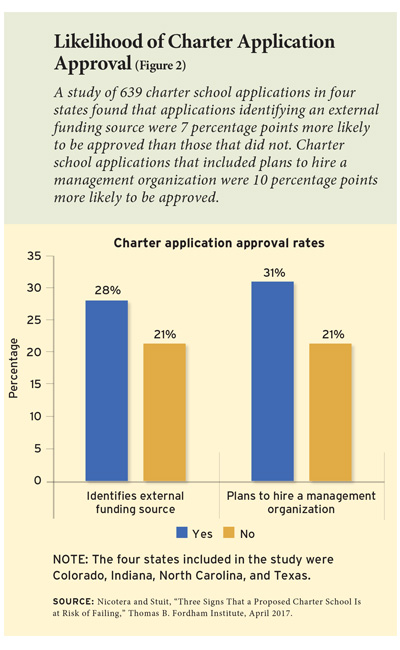

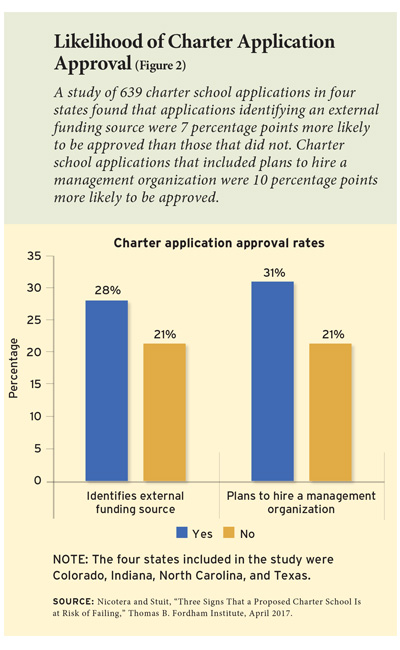

A 2017 Thomas B. Fordham Institute report analyzed 639 charter applications that were submitted to 30 authorizers across four states, providing a glimpse of the tea leaves that charter authorizers read to determine whether or not a school should open. Authorizing is most certainly a process of risk mitigation, as no one wants to open a “bad” school. But some of the study’s findings point to distinct disadvantages for operators who aren’t on the funder circuit or don’t have the high-level connections commanded by the country’s largest CMOs.

For instance, among applicants who identified an external funding source from which they had secured or requested a grant to support their proposed school, 28 percent of charters were approved, compared to 21 percent of those who did not identify such a source (see Figure 2).

“You see single-site schools, in particular with leaders of color, who don’t have access to capital to grow,” said Talbot. “It mirrors small business.” Neophyte entrepreneurs, including some women of color, “just don’t have access to the same financial resources to start up and expand.”

Michele Mason added that the funding problem is not resolved even if the school gets authorized. “Mom-and-pops don’t spend time focusing on [fundraising and networking] and they don’t go out there and get the money. They’re not on that circuit at all.”

“Money is an issue,” agreed Karega Rausch, vice president of research and evaluation at the National Association of Charter School Authorizers (NACSA). “If you look at folks who have received funding from the federal Charter Schools Program, for instance . . . those are the people getting schools off the ground. And this whole process is easier for a charter network that does not require the same level of investment as new startups.”

Authorizing and the Politics of Scale

Charter-school authorizing policies differ from state to state and are perhaps the greatest determinant of when, where, and what kind of new charter schools can open—and how long they stay in business. Such policies therefore have a major impact on the number and variety of schools available and the diversity of leaders who run them.

For example, on one end of the policy spectrum lies the strict regulatory approach embodied by the NACSA authorizing frameworks; on the other end, the open and pluralistic Arizona charter law. Each approach presents very different conditions for solo charter founders, for the growth of the sector as a whole, and, by extension, for the cultivation of political constituencies that might advocate for chartering now and in the future.

Arizona’s more open approach to authorizing has led to explosive growth: in 2015–16, nearly 16 percent of the state’s public-school students—the highest share among all the states—attended charter schools. The approach also earned Arizona the “Wild West” moniker among charter insiders. But as Matthew Ladner of the Charles Koch Institute argues, the state’s sector has found balance—in part because of an aggressive period of school closures between 2012 and 2016—and now boasts rapidly increasing scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, particularly among Hispanic students (see “In Defense of Education’s ‘Wild West,’” features, Spring 2018). It has also produced such stellar college-preparatory schools as Great Hearts Academies and BASIS Independent Schools, whose success has helped the Arizona charter movement gain political support outside of its urban centers.

“When you have Scottsdale’s soccer moms on your side, your charters aren’t going away,” said Ladner.

NACSA’s approach, conversely, is methodical and therefore tends to be slow. Its tight controls on entry into the charter space have come to typify the authorizing process in many states—and have given rise to a number of the country’s best-performing schools and networks of any type, including Success Academy in New York City, Achievement First in Connecticut, Brooke Charter Schools in Boston, and the independent Capital City Public Charter School in D.C. However, some of NACSA’s policy positions could be considered unfriendly to sector growth. For instance, the association recommends that the initial term of charters be for no more than five years, and that every state develop a provision requiring automatic closure of schools whose test scores fall below a minimum level. Such provisions may have the most impact on single-site, community-focused charters, which might be concentrating on priorities other than standardized test scores and whose test results might therefore lag, at least in the first few years of operation.

Certainly, responsible oversight of charter schools is essential, and that includes the ability to close bad schools. “Despite a welcome, increasing trend of closing failing schools [over] the last five years, closing a school is still very hard,” Rausch said. “Authorizers should open lots of innovative and new kinds of schools, but they also have to be able to close them if they fail kids. We can’t just open, open, open. We need to make sure that when a family chooses a school there’s some expectation that the school is OK.”

The issue of quality is anchored in the pact between charter schools and their authorizers (and by extension, the public). Charter schools are exempt from certain rules and regulations, and in exchange for this freedom and flexibility, they are expected to meet accountability guidelines and get results. Over time, authorizers have increasingly defined those results by state test scores.

The issue of quality is anchored in the pact between charter schools and their authorizers (and by extension, the public). Charter schools are exempt from certain rules and regulations, and in exchange for this freedom and flexibility, they are expected to meet accountability guidelines and get results. Over time, authorizers have increasingly defined those results by state test scores.

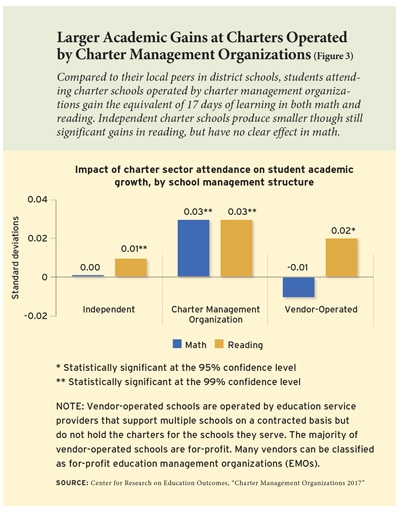

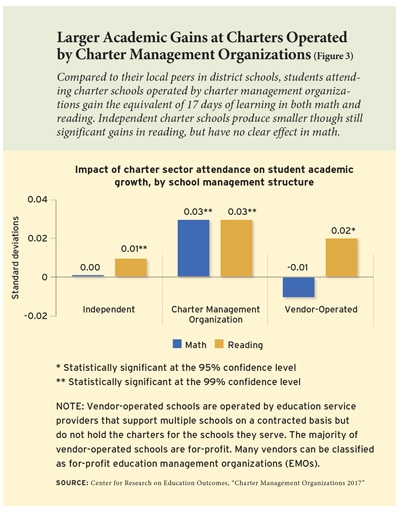

By this measure, the large CMOs have come out ahead. Overall, schools run by them have produced greater gains in student learning on state assessments, in both math and reading, than their district-school counterparts, while the mom-and-pops have fared less well, achieving just a small edge over district schools in reading and virtually none in math (see Figure 3).

But some charter advocates are calling for a more nuanced definition of quality, particularly in light of the population that most standalone charters—especially those with leaders of color—plan to serve. This is a fault-line issue in the movement.

“In my experience, leaders of color who are opening single sites are delivering a model that is born out of the local community,” said Talbot. “We’ve witnessed single-site charters headed by leaders of color serve large numbers of students who have high needs. Not at-risk . . . but seriously high needs—those ongoing emergent life and family conditions that come with extreme poverty,” such as homelessness. “When you compound this with [a school’s] lack of access to capital and support . . . you have this conundrum where you have leaders of color, with one to two schools, serving the highest-needs population, who also have the least monetary and human-capital support to deal with that challenge. And as a result, their data doesn’t look very good. An authorizer is going to say to a school like that, ‘You’re not ready to expand. You might not even be able to stay open.’”

When it comes to attempting a turnaround, standalone schools are again at a disadvantage relative to the CMOs. “What happens with the mom-and-pops is that if they don’t do well early—if their data doesn’t look good—there’s no one there to bail them out,” said Mason. “They don’t have anyone to come and help with the programming. The academic supports. And if they don’t have results early, then they’re immediately on probation and they’re climbing uphill trying to build a team, get culture and academics in place. CMOs have all the resources to come in and intervene if they see things going awry.”

Then, too, a charter school, especially an independent one, can often fill a specialized niche, focusing on the performing arts, or science, or world languages. “As an independent charter school, you have to be offering families something different, . . . and in our case it’s the opportunity for kids to become fully bilingual and bi-literate,” offered Barbara Martinez of HoLa. “It’s not about being better or beating the district. It’s about ensuring that you are not only offering a unique type of educational program, but that you also happen to be preparing kids for college and beyond. For us, [charter] autonomy and flexibility allow us to do that in a way that some districts can’t or won’t.”

In short, the superior performance of CMO schools vis-à-vis test scores does not imply that we should only focus on growing CMO-run schools. Given the resource disadvantages that independent operators face, and the challenging populations that many serve, we would be better advised to provide these leaders with more support in several areas: building better networks of consultants who can straddle the worlds of philanthropy and community; recruiting from non-traditional sources to diversify the pool of potential leaders, in terms of both race and worldview; and allowing more time to produce tangible results. Such supports might help more mom-and-pops succeed and, in the process, help expand and diversify (in terms of charter type and leader) the movement as a whole while advancing its political credibility.

In short, the superior performance of CMO schools vis-à-vis test scores does not imply that we should only focus on growing CMO-run schools. Given the resource disadvantages that independent operators face, and the challenging populations that many serve, we would be better advised to provide these leaders with more support in several areas: building better networks of consultants who can straddle the worlds of philanthropy and community; recruiting from non-traditional sources to diversify the pool of potential leaders, in terms of both race and worldview; and allowing more time to produce tangible results. Such supports might help more mom-and-pops succeed and, in the process, help expand and diversify (in terms of charter type and leader) the movement as a whole while advancing its political credibility.

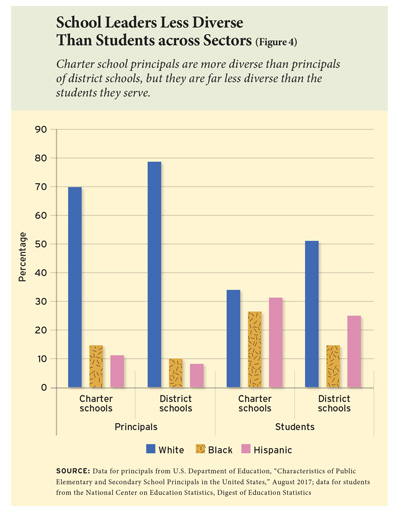

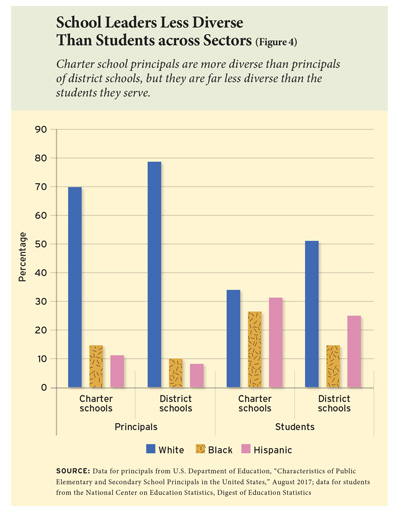

The numbers tell the story on the subject of leadership. Charter schools serve a higher percentage of black and Hispanic students than district schools do, and while charter schools boast greater percentages of black and Hispanic principals than district schools, these charter-school leaders overall are far less diverse than the students they serve (see Figure 4). Though many may view charter schools primarily through the lens of performance, it seems that many of the families who choose them value community—the ability to see themselves in their schools and leaders—substantially more than we originally believed. Diverse leadership, therefore, is a key element if we want to catalyze both authentic community and political engagement to support the movement’s future.

More Is Better

A schooling sector that does not grow to a critical mass will always struggle for political survival. So what issues are at play when we consider the future growth of charter schools, and what role will single sites and a greater variety of school offerings play in that strategy? There’s no consensus on the answer.

A more pluralistic approach to charter creation—one that embraces more-diverse types of schools, academic offerings, and leadership and helps more independent schools get off the ground—might entail risks in terms of quality control, but it could also help the movement expand more quickly. And steady growth could in turn help the movement mount a robust defense in the face of deepening opposition from teachers unions and other anti-charter actors such as the NAACP. (Last year the NAACP released a task force report on charter schools, calling for an outright moratorium on new schools for the present and significant rule changes that would effectively end future charter growth.)

Another viewpoint within the movement, though, points out that the sector is still growing, though at a slower pace and even if there is a coincident reduction in the diversity of school types.

“We know the movement is still growing because the number of kids enrolled in charter schools is still growing,” said NACSA’s Rausch. “It’s just not growing at the same clip it used to, despite the fact that authorizers are approving the same percentage of applications.” He also noted that certain types of growth might go untallied: the addition of seats at an existing school, for instance, or the opening of a new campus to serve more students.

Rausch notes that one factor hampering sector-wide growth is a shrinking supply of prospective operators, single-site or otherwise. “We’ve seen a decline overall in the number of applications that authorizers receive,” he said. “What we need are more applications and more people that are interested in starting new single sites, or more single sites that want to grow into networks. But I’m also not sure there is the same level of intentional cultivation to get people to do this work [anymore]. I wonder if there is the same kind of intensity around [starting charters] as there used to be.”

Many charter supporters, however, don’t believe that an anemic startup supply is the only barrier to sector expansion in general, or to the growth of independent schools. Indeed, many believe there are “preferences” baked into the authorizing process that actually hinder both of these goals, inhibiting the movement’s progress and its creativity. That is, chartering is a movement that began with the aspiration of starting many kinds of schools, but it may have morphed into one that is only adept at starting one type of school: a highly structured school that is run by a CMO or an EMO and whose goal is to close achievement gaps for low-income kids of color while producing exceptional test scores. This “type” of charter is becoming synonymous with the term “charter school” across most of America. Among many charter leaders and supporters, these are schools that “we know work.”

In many regions of the country, these charters dominate the landscape and have had considerable success. However, given the pluralistic spirit of chartering overall, the issue of why they dominate is a salient one. Is it chance or is it engineered? Fordham’s report revealed that only 21 percent of applicants who did not plan to hire a CMO or an EMO to run their school had their charters approved, compared to 31 percent for applicants who did have such plans, which could indicate a bias toward CMO or EMO applicants over those who wish to start stand-alone schools. As Fordham’s Michael Petrilli and Amber Northern put it in the report’s foreword: “The factors that led charter applicants to be rejected may very well predict low performance, had the schools been allowed to open. But since the applications with the factors were less likely to be approved, we have no way of knowing.”

The institutional strength implied by a “brand name” such as Uncommon Schools or IDEA might give CMO schools more traction with authorizers and the public. “The truth is that telling a community that a school with a track record is going to open is significantly easier than a new idea,” offered Rausch. “But it’s important to remember that every network started as a single school. We need to continue to support that. I don’t think it’s either CMO or single site. It’s a ‘both/and.’”

If there is a bias toward CMO charters as the “school of choice” among authorizers, why might that be, and what would it mean for single sites? Some believe the problem is one where the goal of these schools is simply lost in the listening—or lack of it—and that the mom-and-pops could benefit from the assistance of professionals who know how to communicate a good idea to authorizers and philanthropists.

The language of “education people in general, and people of color in education specifically . . . doesn’t match up with the corporate language [that pervades the field and] that underpins authorizing and charter growth decisions,” said Talbot. “I think more [charter growth] funds, philanthropists, foundations, need . . . let’s call it translation . . . so there is common ground between leaders of color, single-site startups, foundations, and other participants in the space. I think this is imperative for growth, for recognition, and for competitiveness.”

What Now?

The future of chartering poses many questions. Admittedly, state authorizing laws frame the way the “what” and “who” of charters is addressed. Yet it is difficult to ignore some of the issues that have grown out of the “deliberate” approach to authorizing that has typified much of recent charter creation.

Some places, such as Colorado, have significant populations of single-site schools, but overall, the movement doesn’t seem to be trending that way. Rausch noted that certain localities, such as Indianapolis, have had many charter-school leaders of color, but the movement, particularly on the coasts, is mainly the province of white school leaders and organizational heads who tend to hold homogeneous views on test scores, school structure, and “what works.” And while some Mountain States boast charter populations that are diverse in ethnicity, income, and location, in the states with the greatest number of charters, the schools are densely concentrated in urban areas and largely serve low-income students of color. Neither of these scenarios is “right,” but perhaps a clever mix of both represents a more open, diverse, inclusive, and sustainable future for the charter movement. In the end, the answers we seek may not lie in the leaves that have grown on the chartering tree, but in the chaotic and diverse roots that started the whole movement in the first place.

Derrell Bradford is executive vice president of 50CAN, a national nonprofit that advocates for equal opportunity in K–12 education, and senior visiting fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Since the company’s inception in 2007, Charter School Capital has been committed to the success of charter schools. We provide growth capital and facilities financing to charter schools nationwide. Our depth of experience working with charter school leaders and our knowledge of how to address charter school financial and operational needs have allowed us to provide over $1.6 billion in support of 600 charter schools that educate 800,000 students across the country. For more information on how we can support your charter school, contact us. We’d love to work with you!

The Charter School Funding Misconception: Who’s money is it?

The Charter School Funding Misconception: Who’s money is it? Since the company’s inception in 2007, Charter School Capital has been committed to the success of charter schools. We provide growth capital and facilities financing to charter schools nationwide. Our depth of experience working with charter school leaders and our knowledge of how to address charter school financial and operational needs have allowed us to provide over $1.8 billion in support of 600 charter schools that have educated over 1,027,000 students across the country. For more information on how we can support your charter school, contact us. We’d love to work with you!

Since the company’s inception in 2007, Charter School Capital has been committed to the success of charter schools. We provide growth capital and facilities financing to charter schools nationwide. Our depth of experience working with charter school leaders and our knowledge of how to address charter school financial and operational needs have allowed us to provide over $1.8 billion in support of 600 charter schools that have educated over 1,027,000 students across the country. For more information on how we can support your charter school, contact us. We’d love to work with you!

In honor of the inspiring teachers who have had a positive impact on their students’ lives, we are launching our Stories of Inspiration campaign to capture the inspiration teachers bring to students every day. During the next five weeks, we’re asking you to tell us your stories. Find out how to submit your inspiring teacher story here.

In honor of the inspiring teachers who have had a positive impact on their students’ lives, we are launching our Stories of Inspiration campaign to capture the inspiration teachers bring to students every day. During the next five weeks, we’re asking you to tell us your stories. Find out how to submit your inspiring teacher story here.