Understanding The Value And Importance Of Public Charter Schools

Understanding The Value And Importance Of Public Charter Schools

Todd Feinburg with Amy Wilkins

In this informative podcast, Todd Feinburg from Radio.com interviews Amy Wilkins, Sr. Vice President Advocacy National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

They answer the question if charter schools are the only alternative for poor, minority and urban students to find alternatives to public schools, why aren’t there more of them, and why don’t Democrats fight for them? They go on to discuss the need for more charter schools as well as the benefits of charter schools in a failing public school system. Finally, they’ll dispel some common myths around charter schools and the charter school movement.

Please listen to the podcast or read the transcript below to learn more.

We think it’s vital to keep tabs on the pulse of all things related to charter schools, including informational resources, and how to support charter school growth and the advancement of the charter school movement as a whole. We hope you find this—and any other article we curate—both interesting and valuable.

TRANSCRIPT

Todd Feinburg: WTIC. You know I love Charter Schools. I want everybody to get a great educate in America and we are far from that point. Joining us now to talk about it is Amy Wilkins, Senior Vice President at the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. How about that? Amy, welcome to WTIC. Thanks for talking to us.

Amy Wilkins: Hi, Todd, how are you this afternoon?

Feinburg: I’m psyched to have you here, so let’s talk Charter Schools and what’s going on. What are the trends going on in the choice world in providing alternatives, particularly in poor communities where it would be nice if people had Charter School options and more choices for their kids for schools. What’s your assessment of where we’re at right now?

Wilkins: Demand far outstrips supply, especially in communities of color. There are far more families who would choose Charter Schools for their kids than currently can, just because of limited space and really, the biggest obstacle we face, to opening more high quality Charter Schools for kids, whether they’re low income, urban, rural, wherever they are, is the facilities question, the school building question. You know, if you’re a district-operated school, the district just gives you a building, right? You get a school building. Charter Schools have to finance their own buildings and finding appropriate and adequate space is really among the things that are holding back growth for these much-needed schools.

Feinburg: And what is the … well, before I ask you that, I’m surprised by what you’re saying about the facility. I understand. I’ve seen Charter Schools that are in church basements and in what were industrial buildings, where they throw up some dividers and make classrooms and those aren’t ideal, but what you find out when you see those schools in action is that the facilities maybe are over-emphasized in our public schools. And what’s really important is having a great education in whatever kind of walls you can find.

RELATED ARTICLE: BEST PRACTICES FOR CHARTER SCHOOL FACILITIES FINANCING

Wilkins: Oh, absolutely. You know, what matters most, what is the heart of any school are the teachers and the curriculum, I would agree with you 100% on that, Todd. But, I also think the kids whose families choose Charter Schools deserve libraries, labs, playing fields, all of those facilities as well. So, yes, better to go to a strip mall and get a really strong educate, than to go to a palace where you get a not so strong educate. In the best of all worlds, you go to a high-quality Charter School that has a lab, a library, a playing field, all of those facilities.

Feinburg: So, how do Charter Schools get the buildings?

Wilkins: Well, you know, too often they have to buy a building and then they face the same mortgage problems that all of us face when we want a mortgage and the problem, as you know, is Charter Schools, when they’re looking for a building, are often brand new and don’t have much of a track record to stand on, so it’s hard for them to get financing or they pay rent for a building. And what happens then, as you know, you have district-operated schools where their building is just free, it’s given to them by the district. Charter Schools, when they’re paying rent or financing a mortgage are having to take funds that would otherwise be directed to their instructional programs and pay building costs.

Feinburg: Have Charter Schools proven to be worth the investment? We hear all this conflicting information about whether they’re actually a successful alternative or not.

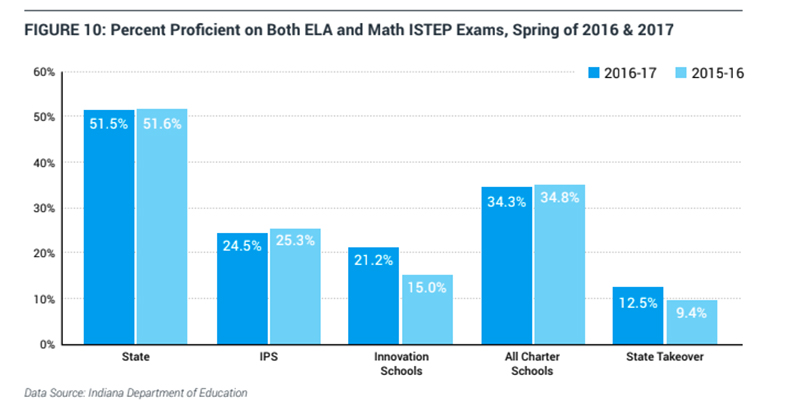

Wilkins: I think like anything, we have some really great Charter Schools and we have some Charter Schools that I think should be closed. But, in general, the general trend suggests particularly for urban kids and for kids of color, Charter Schools are their very best bet. We have solid evidence that kids, those kids in particular, gain months of learning over their peers in district-operated schools. So, the trend seems to be telling us, yes, this is really important from a data point of view, from a student achievement point of view, they are absolutely the right answer. From a parenting point of view, they are the right answer as well. I mean, parents deserve a choice. Not every school fits every child, you know? You may want a different type of curriculum for your child. Your child may have special needs that the district schools are unable to meet. So, both from an academic point of view and from the point of view of parents having some control over the kind of educate their kids get, Charter Schools are absolutely a vital part of kind of a healthy public education ecosystem.

Feinburg: We’re talking to Amy Wilkins on Charter Schools. I love talking about Charter Schools because my belief is, particularly in urban areas, that there is a crisis going on, and I don’t feel, Amy, as a country that we can afford to have millions of kids, rich, poor, minority, white, whatever … we can’t afford to have millions of kids not getting a great education.

Wilkins: Absolutely not. I mean, at bottom, it’s sort of inhumane and, you know, no adult should look at a child who’s not getting an education and feel good about it. But, I mean, there are certainly strong implications for our future economy, including who’s going to pay your Social Security and mine, Todd. There are big implications for national security. Educating our kids is the foundation of our future and Charter Schools are a proven sort of winner in that for our kids and so, to me, it’s a no-brainer, that we just have to do it. We have to do well and we have to do more of it.

Feinburg: Do you see a way to make this argument, though, for cities? So, in Connecticut, we have so many cities and they’re not particularly large, but they are part of a pattern of a city being a place where minority kids, poor kids are essentially stored and not given an opportunity to get out. It just strikes me, as you say, as some kind of human rights violation, if you want to argue from the humanity point of view, that the system is rigged to be mediocre, at best and oftentimes worse and there’s no economic opportunity. There’s really not a way out and that drives a lot of minority kids into gangs and bad behavior that puts a lot of boys into prison. And how does that pattern get broken through education, because that’s the only tool I think we have available?

Wilkins: No, you’re absolutely right. Education is the surest way out of poverty and the strongest weapon, I think, we have against racism. It really is up to … I hate to say this, it’s up to communities. You know, they have to stand up on behalf of their kids and demand something better, demand something different. Now, you could also … I don’t know, this is like being really kind of out there … you know, you saw the kids at Parkland saying, “We’re not happy with the kind of safety of our schools and we’re afraid of guns in our schools.” I think, you know, the kids know when they’re being short-changed. We really sort of have to start talking to the kids about how they feel about the schools they’re going to and, unfortunately, they’re not old enough to vote, but I think conversations … if elected officials had conversations with kids at some of these schools, some of the kids I talk to and hear what goes on in their schools, I think that would spur some action that we’ve yet to see.

Feinburg: Have you ever seen that kind of thing going on where there are public displays of rebellion or unrest over the idea that oppression, the educational oppression of minority students?

Wilkins: Well, I don’t know if I would call it unrest. I have seen groups of students in various parts of the country … I know it’s happened in Wisconsin. I know it’s happened in California, who do lobby days and go to their state legislatures to lobby and testify about the conditions in their schools. One could certainly see the same things happening at School Board meetings and City Council meetings in Connecticut, if there were folks willing to help these kids begin to organize.

Feinburg: Yeah, but there has to be a spark of something bigger because the rigged education system, the partnership between the Democratic party and the Education Unions, there is this fixed system that says this is the only way education can happen, and we live in times where we need educational agility, where policy can change quickly, where schools can adapt over the very short term to the needs of the kids. How do we get from here to there if there’s no model if there’s nothing for people to look at and say, “We want that.”

Wilkins: Well, there are models. I mean, that’s the thing. In Connecticut, for example, you have the Amistad Charter Schools which are among the best in the country and people should really go see them. They have done a wonderful job with those schools. So there are things … part of this … part of the challenge here is people don’t … and I’ve been doing education for years, and years, and years. What’s so sad is that people really don’t see schools beyond the schools that they attended and the schools their children have attended and they don’t know that something else is out there, that something else can be better and you know, part of the responsibility of groups like mine, in doing interviews like this one, is to let people know there are better alternatives and to say that it’s easy to create one, it’s easy to sustain one, I would be lying. But you know, there are better things, but like most better things, they require work and commitment.

Feinburg: Amy Wilkins is the Senior Vice President at the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. So, what exactly do you folks do?

Wilkins: We represent in Washington, primarily. The Charter Schools out there in America, we lobby Congress to ensure that there’s funding to start more and better Charter Schools.

Feinburg: So, the Federal dollars are a critical part?

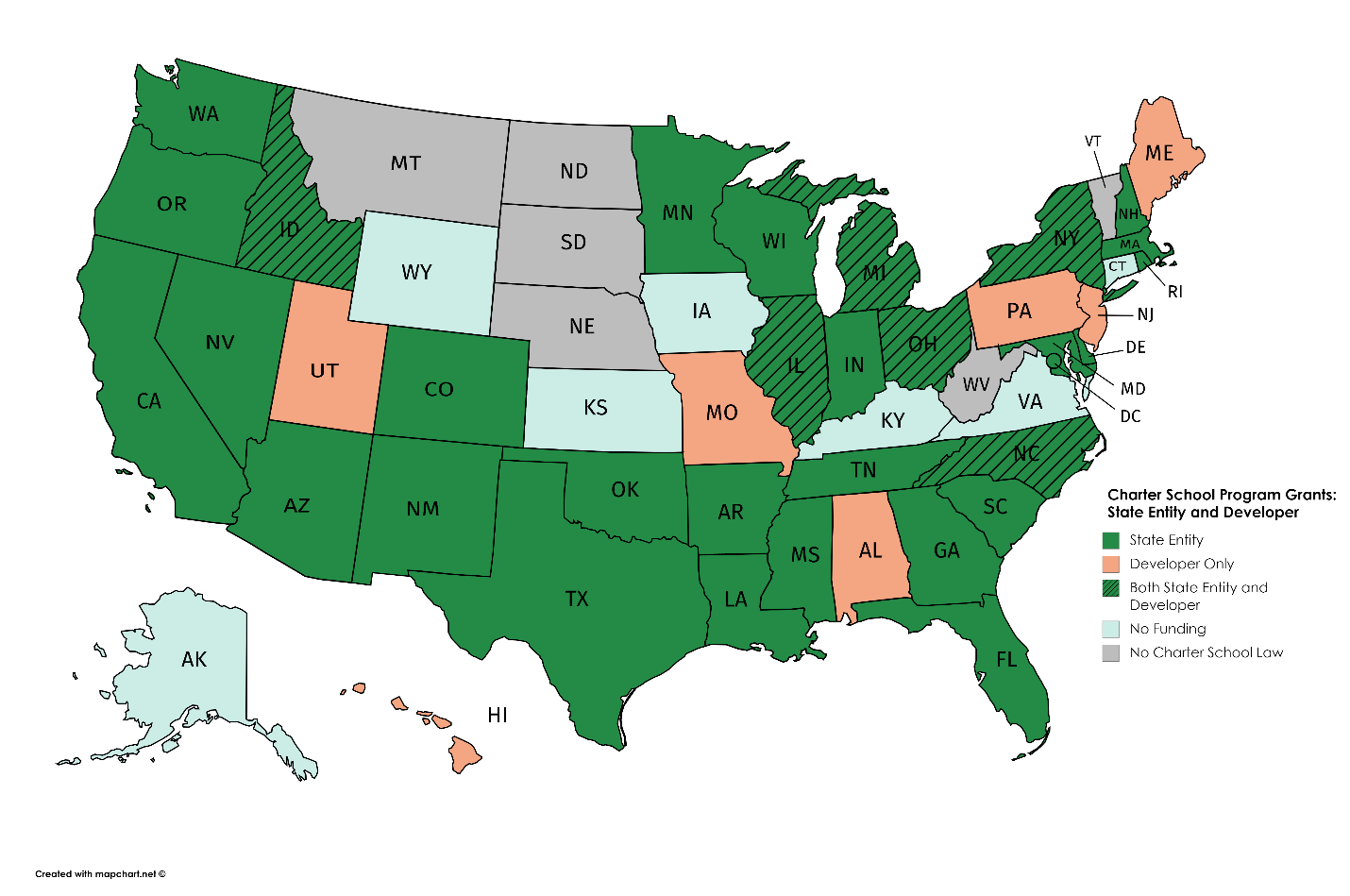

Wilkins: The Federal dollars really are start-up dollars. Once you’ve started, then you really are reliant on state and local funding, but the Federal government does supply … it’s a program called the Charter Schools Program and it supplies seed money for new Charter Schools to get started.

Feinburg: What are the … can you shoot down the basic arguments against Charter Schools, the kind of superficial ones that have appeal to people who aren’t very involved, and they hear about how, for example, that Charter Schools are taking dollars away from the public schools, it’s an attempt to destroy the public schools.

Wilkins: Well, that just doesn’t make any sense because Charter Schools are public schools. Charter Schools are part of the public school system, so I don’t understand how they could take money away from a system that they’re already a part of. It’s just a nonsensical argument that the Teacher’s Unions have sort of … it’s a catchy phrase, but it means nothing.

Feinburg: How about Charter Schools just have to … they get to pick whatever kids they want. They don’t have to worry about the special ed kids?

Wilkins: That’s not … in fact, Charter Schools currently are serving a slightly higher percentage of special needs kids than our traditional public schools, so that’s just not true. Charter Schools serve as many and, in some cases, a few more special needs kids than do traditional public schools.

Feinburg: I forget what else the arguments are. Is there one more you can give us?

Wilkins: Yeah, that they’re a plot to tear down the traditional public school system. At this point, Charter Schools make up less than 5% of all schools in the country.

Feinburg: So it’s a failing plot?

Wilkins: Yeah, we’re doing a pretty bad job. I mean, if the traditional public schools, which are educating 95% of the children are so scared of something that only represents 5%, there’s something deeper going on there, you know? And I think that that’s one of the things we really have to understand about Charter Schools. The demand for Charter Schools, to me, reads like an indictment of the traditional public school system. If everything were hunky-dory in traditional public schools, there wouldn’t be this enormous demand for Charter Schools. And so when the traditional public schools point to Charter Schools and say, “Oh, they’re a problem, they’re a problem, they’re a problem,” they really should turn and look more in the mirror to say, “Why are these schools even existing? Why do people demand them?” They demand them because public schools have fallen so far short for so many kids.

Feinburg: Amy Wilkins, National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. What’s the website?

Wilkins: It’s www … I have to get some help here, www.publiccharters.org.

Feinburg: What is it?

Wilkins: It’s publiccharters.org.

Feinburg: Publiccharters.org. Amy, thank you so much. Great to talk with you.

Wilkins: Thank you so much. It’s great to talk to you. Have a good afternoon. Bye-bye!

Feinburg: Bye-bye. I hit her with a tough surprise question at the end.

The 5 Essential Steps to Charter School Facilities Planning

Charter school facilities planning can be daunting. If you think that finding the perfect facility for your charter school seems like a huge, complicated undertaking, you’re in good company. This handy, information-packed guide, will help as you move towards realizing your facility expansion or relocation goals.

In it, we cover these five essential charter school facility planning steps—in detail:

Plan – Begin planning at least one year in advance

Plan – Begin planning at least one year in advance- Fund – Understand your options to make savvy decisions

- Acquire – You know what you can afford and how you’ll pay for it … now go get it

- Design – Partner with experts to design your new space

- Execute – Let the construction begin and get ready to move in

Since the company’s inception in 2007, Charter School Capital has been committed to the success of charter schools. We provide growth capital and facilities financing to charter schools nationwide. Our depth of experience working with charter school leaders and our knowledge of how to address charter school financial and operational needs have allowed us to provide over $1.8 billion in support of 600 charter schools that have educated over 1,027,000 students across the country. For more information on how we can support your charter school, contact us. We’d love to work with you!

Since the company’s inception in 2007, Charter School Capital has been committed to the success of charter schools. We provide growth capital and facilities financing to charter schools nationwide. Our depth of experience working with charter school leaders and our knowledge of how to address charter school financial and operational needs have allowed us to provide over $1.8 billion in support of 600 charter schools that have educated over 1,027,000 students across the country. For more information on how we can support your charter school, contact us. We’d love to work with you!

Plan – Begin planning at least one year in advance

Plan – Begin planning at least one year in advance