Diversity in America’s Traditional Public and Public Charter School Leaders

Editor’s Note: This article about diversity among public school leaders including public charter school leaders, was originally published here on September 9, 2019 by The 74 and written by Laura Fay.

We think it’s vital to keep tabs on the pulse of all things related to charter schools, including informational resources, and how to support school choice, charter school growth, and the advancement of the charter school movement as a whole. We hope you find this—and any other article we curate—both interesting and valuable.

As Schools Diversify, Principals Remain Mostly White — and 5 Other Things We Learned This Summer About America’s School Leaders

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

Reports released this summer offer new insight into America’s school principals, from their racial diversity to how turnover affects student achievement.

The new papers add to a growing body of research about principals but also raise new questions, said Brendan Bartanen, an assistant professor at Texas A&M University and co-author of recent reports on principal diversity and principal turnover.

“We know that principals matter,” Bartanen told The 74. “We still don’t have a great understanding of the specifics of that — how do they matter, what are the specific things that they do, what are the ways that we could train them better and provide them better development?”

Amid growing concern about teacher diversity — America’s teachers are about 80 percent white — Bartanen’s research shows that black principals are more likely to hire black teachers to work in their schools. Having just one black teacher in elementary school can improve a number of outcomes for black students. But federal data show that principals are overwhelmingly white.

Here are six things we learned about America’s principals this summer.

1. Principals are overwhelmingly white, despite increasingly diverse students.

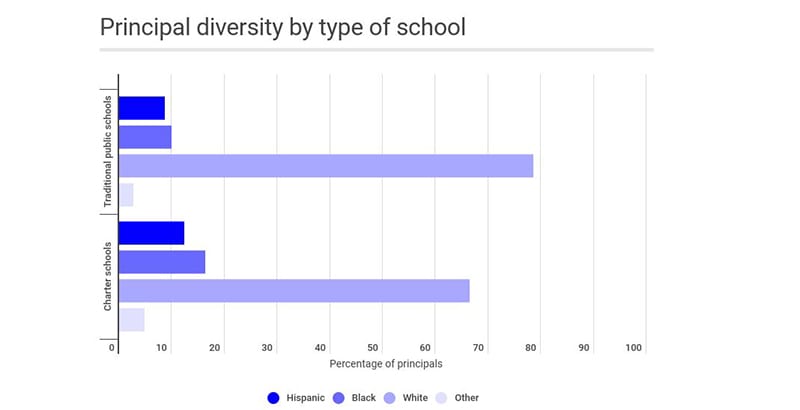

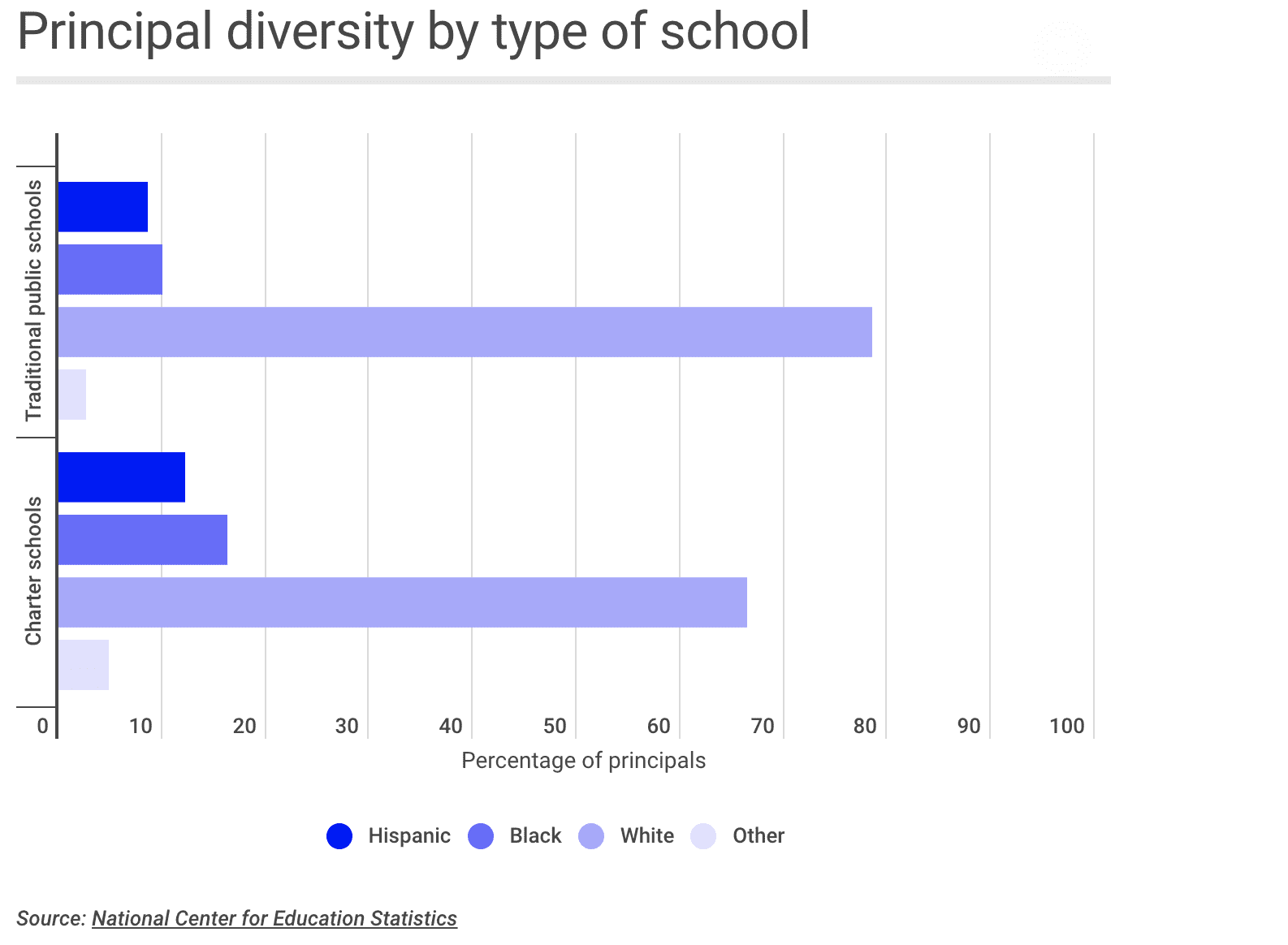

Although more than half of U.S. students are racial minorities, about 78 percent of public school principals are white, according to 2017-18 survey data collected by the National Center for Education Statistics and released in August. That mirrors the makeup of the American teaching corps, which is about 80 percent white.

The remaining principals were about 8.9 percent Hispanic, 10.5 percent black and 2.9 percent other races. Urban districts were more likely to have principals of color than their rural, town and suburban counterparts.

Most nonwhite principals were in high-poverty schools. At schools where 75 percent or more of students are eligible for free or reduced-price lunches, almost 60 percent of teachers were white while 16.5 percent were Hispanic and 21 percent were black, the NCES data show. (NCES did not break down responses in the “other” category, which includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and two or more races.)

2. Charter school leadership was slightly more diverse than principals in traditional public schools.

In charter schools, 66.5 percent of principals were white, while 12.3 percent were Hispanic and 16.3 percent were black, according to the NCES numbers.

A recent study by the Fordham Institute found that charters also tend to employ more black teachers than district schools do.

3. Black principals are more likely to hire and retain black teachers.

When a school gains a black principal, black teachers are more likely to be hired and retained, according to a working paper written by Bartanen and Jason A. Grissom of Vanderbilt University and released in May by the Annenberg Institute at Brown University.

Schools that changed from a white to a black principal saw an average increase in black teachers of about 3 percentage points because black teachers were more likely to be hired and to stay in their positions.

Bartanen and Grissom used teacher data from Missouri and Tennessee, where there was not enough information to gauge the effects of switching from white to Latino principals. The working paper has not been peer-reviewed and is subject to change.

4. Most principals say their training left them well prepared.

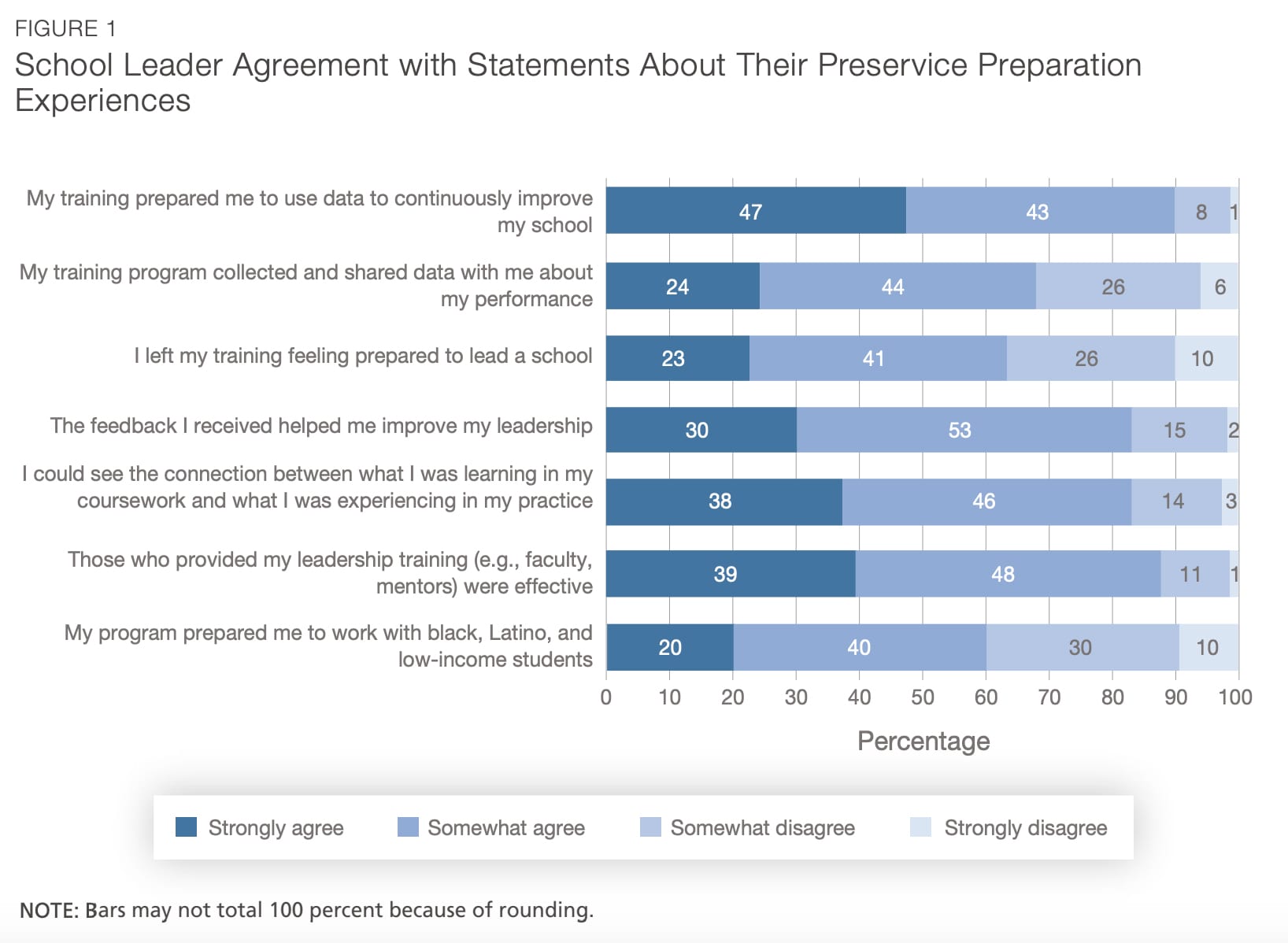

A report released by RAND used survey data to look at teachers’ attitudes about their preparation programs.

Overall, principals reported that their training prepared them well to lead a school, with more than 80 percent responding that they could see a connection between their coursework and practice as school leaders.

Additionally, the RAND researchers found a positive relationship between the amount of field experience educators had and how they rated their training programs. Both teachers and principals who had more field experience reported feeling more prepared for their work in schools.

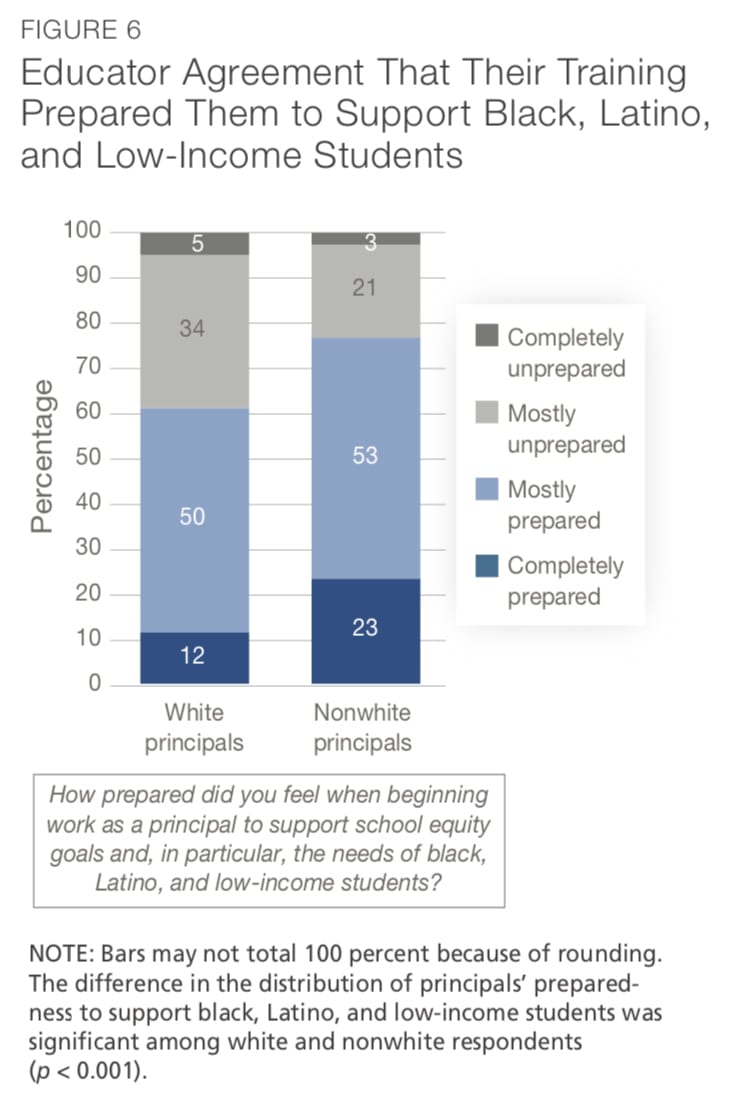

5. But 39 percent of white principals say they were not well prepared to support black, Latino and low-income students.

When asked whether their preservice training prepared them to support black, Latino and low-income students, 62 percent of white principals agreed, compared with 76 percent of nonwhite principals, according to the RAND report. The leaves about 2 in 5 white principals who said they were “mostly” or “completely” unprepared to work with poor and minority students.

There was a similar gap among teachers.

6. Principal turnover tends to hurt student achievement — but not always.

6. Principal turnover tends to hurt student achievement — but not always.

The average rate of principal turnover is around 18 percent, according to NCES data. The schools principals left typically saw declines in math and reading scores, but the reason for the leadership change affected the outcomes, according to a new report published in June in Education Evaluation and Policy Analysis. For example, in cases in which the principal was demoted, student achievement stayed the same or improved. Meanwhile, students whose principals moved to other schools or to district-level positions saw a decrease in their math and reading scores.

The takeaway is that districts should be strategic about retaining strong principals but not afraid to remove low-performing ones, said Bartanen, who wrote the paper with Grissom and Laura K. Rogers.

Disclosure: The Carnegie Corporation of New York, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Walton Family Foundation and Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation support both RAND and The 74.

Since the company’s inception in 2007, Charter School Capital has been committed to the success of charter schools. We help schools access, leverage, and sustain the resources charter schools need to thrive, allowing them to focus on what matters most – educating students. Our depth of experience working with charter school leaders and our knowledge of how to address charter school financial and operational needs have allowed us to provide over $2 billion in support of 600 charter schools that have educated over 1,027,000 students across the country. For more information on how we can support your charter school, contact us. We’d love to work with you!

Since the company’s inception in 2007, Charter School Capital has been committed to the success of charter schools. We help schools access, leverage, and sustain the resources charter schools need to thrive, allowing them to focus on what matters most – educating students. Our depth of experience working with charter school leaders and our knowledge of how to address charter school financial and operational needs have allowed us to provide over $2 billion in support of 600 charter schools that have educated over 1,027,000 students across the country. For more information on how we can support your charter school, contact us. We’d love to work with you!